C.S. Morrissey: Global Theatre -- award-winning newspaper column

Browse archive of 2016 & 2015 columns

Browse archive of 2014 & 2013 columns (and earlier writings)

Read the latest column:

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

The Roman statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero teaches us a word we can use to toast Canada's sesquicentennial, writes C.S. Morrissey.

The Roman statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero teaches us a word we can use to toast Canada's sesquicentennial, writes C.S. Morrissey.

As Canada celebrates the 150th anniversary of Confederation, we have the chance to use a rare word: sesquicentennial.

The Latin word sesqui turns the number following it into “one and a half” of whatever that number is. Since a centennial marks a one hundred year anniversary, a sesquicentennial makes it one hundred and fifty.

While the Latin word centum can mean “one hundred,” it can also refer to an indefinitely large number. So, if you say you ate a hundred potato chips, we know you mean you simply lost count.

Although sesqui occurs in Latin literature most often as a prefix, it does show up a single time as an independent word. The philosopher and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero, when discussing metrical patterns in poetry, uses it to describe a ratio between long and short syllables.

In poetry, the two short syllables in the pattern called a dactyl are considered to be equal in length to the one long syllable that comes before them. That’s why the word dactylus, which means “finger,” is a good name for this pattern.

Take a look at the index finger in your left hand. You will notice the two short parts of the finger follow the one long part. Is the length of the two equal to that of the one?

Another pattern in poetry is the iambus, in which there is a short syllable and a long syllable. Cicero, doing the math, notes the long syllable is twice as long as the short one.

The third poetic pattern Cicero mentions is called a paean, in which there are four syllables: three are short, and one is long. Cicero, again doing the math, uses sesqui as a standalone word to describe the ratio of the short syllables to the long syllable as “one and a half.”

I am surprised we don’t have more examples of sesqui used as an independent word. In our day, it could be quite a handy term for ordering a “super-sized” portion of anything.

For example, a regular six-ounce serving of wine could be upgraded to a nine-ounce portion. Wouldn’t it make sense to call that portion a sesqui, making use of the elegant Latin word as upscale shorthand?

If enough of us start ordering food and drink using sesqui, then over time I think it could catch on as a new slang term in English. In any event, I will be making use of it to toast Canada’s sesquicentennial, with sizable portions appropriate for the occasion.

By the way, the word paean is also a word referring to any joyous song of tribute. No doubt the ancients named the metrical pattern used in composing such songs after the very name for those songs: paeans.

If we were to toast Canada’s sesquicentennial with a sesqui of our favorite beverage, what could we sing about in our paean? Since we are in the mood to “super-size” (excuse me, I mean “sesqui-cize”), we need to go above and beyond what our national anthem teaches us about Canada.

For me, the best way to learn about Canada’s history is to study the political and philosophical arguments at its birth. The indispensable book for this purpose is called Canada’s Founding Debates.

Louis Riel, one of Canada’s most famous historical figures, led the Red River Resistance when the Hudson’s Bay Company, without a vote from the people affected, sought to transfer Rupert’s Land (and thereby the Red River Colony) to Canada.

In a footnote to one of Riel’s speeches in Canada’s Founding Debates, William Gairdner notes the debate at the time was whether rights are “real concrete claims and protections against particular governments or abstract universal rights of all men regardless of place or history.”

Gairdner characterizes the “more English view” as seeing rights as concrete and particular, whereas the “more French view” considers rights as universal and abstract. The Irish statesman Edmund Burke warned that abstract “metaphysical rights” easily lend themselves to being redefined by governments to mean almost anything.

This debate from Canada’s founding is still with us today. Considering the matter, Riel said (March 16, 1870): “After all, there is here in some respects distinction without a difference. We complain not because we are British subjects merely, but because we are men. We complain as a people — as men — for if we were not men we would not be British subjects.”

Perhaps the Canadian genius for compromise, bringing together English and French, is to find the truth in both views. So, how about a paean to Canada’s sesqui of rights?

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

Although conscious of the ways in which the Church needed to be reformed, Erasmus profoundly differed from Luther by not attacking the authority of the Pope or Catholic doctrine, writes C.S. Morrissey.

Although conscious of the ways in which the Church needed to be reformed, Erasmus profoundly differed from Luther by not attacking the authority of the Pope or Catholic doctrine, writes C.S. Morrissey.

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam reportedly said, “When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left, I buy food and clothes.”

Book lovers everywhere feel a profound affinity with Erasmus. They have always loved this quotation, because they can readily relate to the sentiment. But did Erasmus, a Renaissance humanist who died in 1536, really starve himself in order to buy books?

Perhaps we should look at what Erasmus actually said. It was written in Latin, in a letter to Jacob Batt, dated April 12, 1498: “Ad Graecas literas totum animum applicui; statimque, ut pecuniam acceptero, Graecos primum auctores, deinde vestes emam.”

A more accurate translation of Erasmus’ famous saying would thus be: “I have turned my entire attention to Greek. The first thing I shall do, as soon as the money arrives, is to buy some Greek authors; after that, I shall buy clothes.” (Collected Works of Erasmus, Vol. 1)

Now that makes more sense. I too, on many occasions, rather than update my wardrobe, have elected to buy more books instead. Besides, how many garments does an absent-minded scholar need? It’s much easier simply to wear the same thing, especially when you are busy thinking about the argument of a fine new book you just bought.

Erasmus produced a Greek and Latin scholarly edition of the New Testament, which became a bestseller. When Martin Luther made his German translation of the Bible, he used Erasmus’ newest edition of the Greek text.

One of the best new books coming across my desk recently is The Stoic Origins of Erasmus’ Philosophy of Christ, written by the scholar Ross Dealy. It makes a fascinating argument about the profound philosophical reasoning at the heart of Erasmus’ deepest convictions.

Erasmus was ordained a Catholic priest at the age of 25. While Erasmus was critical of notorious abuses within the Catholic Church, he nonetheless famously disagreed with Luther about how to deal with such problems.

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. From those tumultuous times beginning in 1517, Erasmus is an historical figure worth revisiting. There is still much to be learned from him, especially since as “Prince of the Humanists” (so he has been called) he possesses much scholarly wit and wisdom.

With the passage of time, Erasmus’ steering of a via media (“middle course”) in the midst of the bitter controversies of his day can be better appreciated. Although conscious of the ways in which the Church needed to be reformed, Erasmus profoundly differed from Luther by not attacking the authority of the Pope or Catholic doctrine.

Yet by fair-mindedly pursuing the moderate way of the “middle course,” Erasmus ended up pleasing almost no one. He angered the partisans of both sides, who only wanted to fight with each another. What then made Erasmus tick? How did he keep his cool when others sought to sow anger and division?

The Stoic Origins of Erasmus’ Philosophy of Christ describes how Erasmus drew upon fundamental principles of Stoic philosophy in order to arrive at his sophisticated theological views; for example, on Christ’s suffering in Gethsemane.

Many of Erasmus’ contemporaries adopted a one-dimensional view of ancient Stoic philosophy. In this caricature, Stoicism suppresses all emotion, in order to exalt the one dimension of reason.

This misunderstanding of Stoicism still survives today. But consider how not even Star Trek’s Mr. Spock is capable of being such a “one-dimensional Stoic,” since emotion is still an essential part of Spock’s half-human make-up, which he eventually learns how to properly integrate into his full personality. How could fully human ancient Stoics be any different?

Dealy presents abundant evidence for Erasmus’ keen understanding of a “two-dimensional” view of Stoicism, which embraces both reason and emotion as appropriately human. The spirit is not meant to ruthlessly vanquish the flesh.

“While earlier humanists had relentlessly criticized Stoic coldness and irrelevance to human emotions and human endeavours,” Dealy writes, “with Erasmus it is Stoicism that unfolds human feelings and the uniqueness of one’s personality and shows their relationships to higher truth.”

To understand Christ in Gethsemane, then, we must appreciate he had real human feelings, including a real fear of death. That at the same time Christ also experienced joy in his divine nature should not lead us to deny those very real emotional aspects of his incarnate human experience.

Erasmus knew that classical reasoning has many excellent resources to help us understand divine mysteries better. No wonder the guy liked books so much.

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

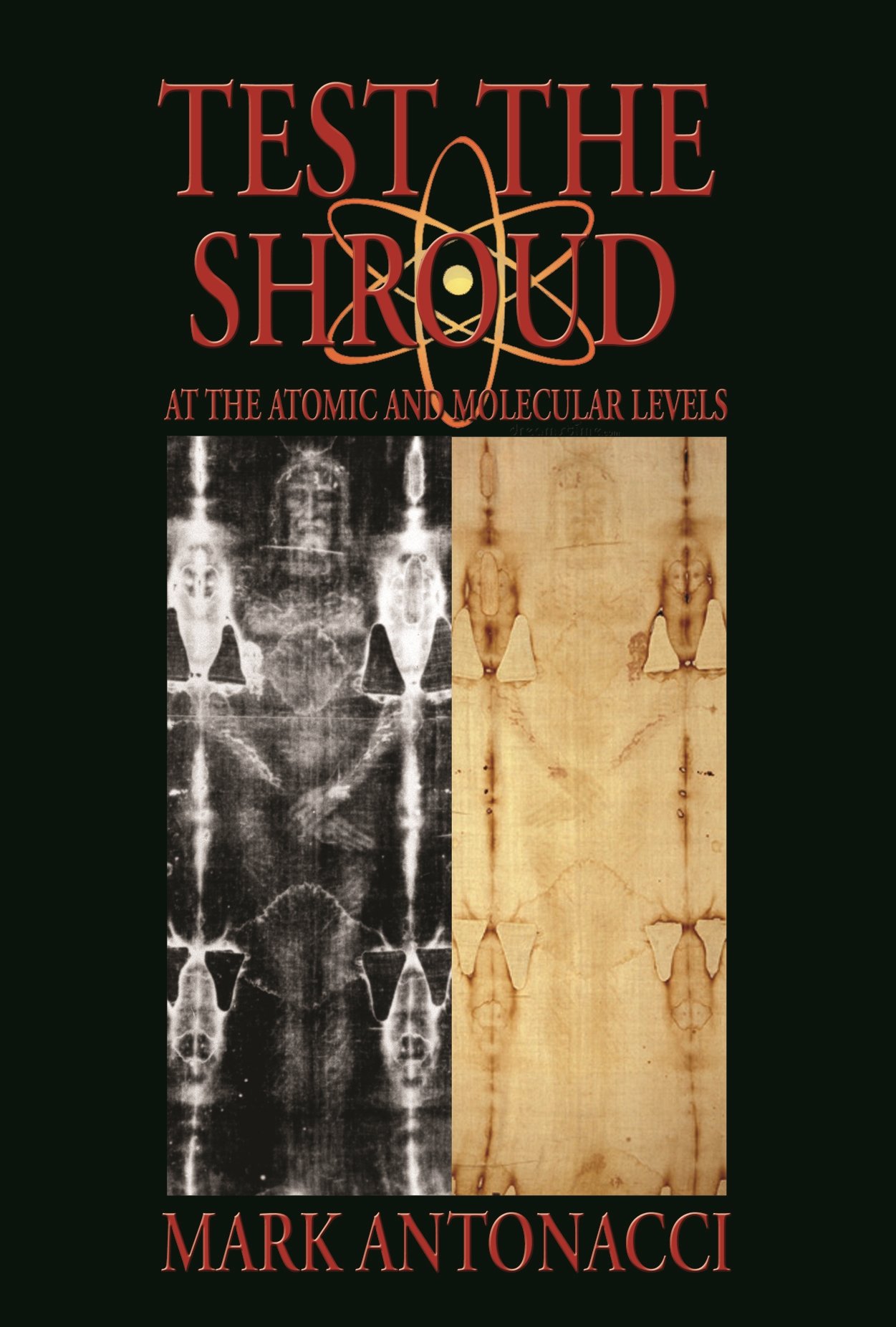

The image on the Shroud of Turin, which many believe to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, presents an interesting puzzle, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Image credit: Mark Antonacci)

The image on the Shroud of Turin, which many believe to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, presents an interesting puzzle, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Image credit: Mark Antonacci)

The image on the Shroud of Turin, which many believe to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, presents an interesting puzzle. The image is of a scourged and crucified man. The puzzle concerns how the image became encoded onto the cloth.

The inner part of the cloth would have lain on top of the body. Yet no paints, powders, or pigments could have produced the body image that is on the cloth, at least according to those who have studied the Shroud in detail.

Mark Antonacci is an attorney who has investigated the Shroud for decades and who has authored Test the Shroud (2016) and The Resurrection of the Shroud (2000). He notes a great deal of “objective and independent evidence” is available about the puzzling Shroud image.

For example, the various details of the images of coins and flowers also encoded onto the Shroud date it to the appropriate time and place. But they do so in such sophisticated ways that it is very unlikely that any forger could have foreseen producing such results.

Antonacci and others thus contend the Shroud is not a medieval fake, but rather a sacred relic. It possesses an abundance of curious features that forgery does not explain. Multiple, convergent lines of evidence suggest instead that no technique other than radiation could have produced the image on the cloth.

This is perhaps the most interesting aspect of the puzzle about the Shroud of Turin. What is the radiation source that could have been involved in the production of the image? It seems only particle radiation could account for the coin and flower images, for example.

Even more significantly, the carbon-14 dating of the Shroud done in 1988 is called into question by the particle radiation hypothesis. In particular, the release of neutrons during the radiation event would produce effects consistent with the data measured in 1988 by the laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Tucson.

Although those researchers concluded that it was “95% certain” the Shroud “originated sometime between the years 1260 and 1390,” their measurements could also be explained by neutron absorption.

Moreover, the neutron absorption hypothesis is testable. That is, the hypothesis could be disproven by further tests on the Shroud. Without doing such tests, one cannot be certain that the Shroud is a medieval forgery.

The neutron absorption hypothesis points to another type of event. The possibility of neutron emission is consonant with a burst of radiation that would have happened if Jesus’s body were to dematerialize from its tomb.

Antonacci estimates two quintillion neutrons would have been emitted from Jesus’s body in the tomb from random locations in the body as it disappeared from the tomb. The image could not have been produced by a radiation source from outside the body. The source was from inside the body.

Recently, I attended a daylong seminar in which university research physicists questioned Antonacci. They had the expertise to evaluate the hypothesis that the Shroud was irradiated with neutrons. If the image on the Shroud was indeed formed by a radiation burn, then a brief burst of radiation from within the body would have to have collimated up and down to form the high resolution image.

The hypothesis is testable. The Shroud could be examined for isotope anomalies that would confirm the hypothesis of a radiation burst. Not only might this explain the carbon-14 dating results from 1988, it could also point to a unique historical event as the source of the image production.

The physicist John Jackson suggested a technical possibility, which has been developed and discussed by Thaddeus Trenn (University of Toronto) under the name of “weak dematerialization.”

In such dematerialization, the bonds between the protons and neutrons in the body of Jesus would have broken apart. As the body disappeared, the Shroud image would have been produced by the particles as the Shroud fell through them.

“The conjecture implies that the carbon-14 distributions would not be uniform on the Shroud,” says philosophy professor and Shroud researcher Phillip Wiebe (Trinity Western University). This conjecture “could be readily examined in a non-invasive way.”

Skeptics deny Jesus’s body disappeared from the tomb and then reappeared in a resurrected form. But further scientific testing of the Shroud could show definitively whether or not the puzzling Shroud image was produced by a radiation burst.

The conjecture is testable, and it offers a more intriguing possibility than assuming the image is a medieval forgery produced by an unknown method.

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

Making real art is hard work, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Image credit: Catholic Art Guild logo / CatholicArtGuild.org)

Making real art is hard work, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Image credit: Catholic Art Guild logo / CatholicArtGuild.org)

Perhaps there is a philosophical way to identify what is objectively beautiful. Could beauty be something shared by many?

How might people participate in a communal experience of beauty? A group of people could also participate in a collective delusion. How can we tell the difference?

Recently, I was invited to meet a community of artists who are very concerned about this question. They gather together, at St. John Cantius Church in Chicago, to debate and discuss ways to deal with our culture of fakes. Known as the Catholic Art Guild, they support one another in the creation of artworks of real beauty.

There is such a thing as fake beauty. Unlike fake news, or fake history, it is something much harder to submit to fact checking and philosophical analysis. Matters of truth can be expressed in propositions, but the objective assessment of beauty is something subtle indeed.

The first step is to identify fake beauty in its most pandemic form. For this, we can turn to one of our greatest contemporary philosophers on aesthetic matters, Sir Roger Scruton. Sir Roger diagnoses the sickness with a single word: “kitsch.”

“Kitsch is fake art, expressing fake emotions, whose purpose is to deceive the consumer into thinking he feels something deep and serious,” says Scruton in an essay written in 2014, for the BBC News Magazine.

Fake art is hard to define, but we can know it when we see it. Sir Roger gives some simple examples, showing us we are capable of basic aesthetic judgments. “The Barbie doll, Walt Disney’s Bambi, Santa Claus in the supermarket, Bing Crosby singing White Christmas, pictures of poodles with ribbons in their hair,” offers Scruton.

But wait a minute, what if you like some of those things? Perhaps then you immediately feel yourself objecting to the philosophical distinction between “fake beauty” and the real thing.

Maybe “kitsch” is simply a nasty insult, offered by a grumpy old man, who thinks his subjective preferences for beauty are better than yours.

No, the philosopher is asking us to step back from our experiences and to reflect on them. For the moment, let us lay the aside the feeling about whether we are offended or not when someone suggests we could be too ardently attached to kitschy art.

Sir Roger reflects on the significance of our experience of Christmas kitsch: “At Christmas we are surrounded by kitsch — worn out clichés, which have lost their innocence without achieving wisdom.”

It’s not that kitsch isn’t attempting to be beautiful. It desperately wants to be the beauty for which we seek. If we didn’t need beauty so badly, we wouldn’t find comfort in fake beauty. Often it seems to be the only thing available to meet our needs.

“Children who believe in Santa Claus invest real emotions in a fiction,” writes Scruton. Something similar happens when we feel comfort from our repose in fake beauty.

No doubt the comforting experience is real. Yet this is its subjective dimension, which the philosopher is seeking to measure, against a more objective standard.

Think about what we have all experienced: namely, growing up, and not believing in Santa Claus anymore. What does the Christmas kitsch involving Santa make us feel?

“We who have ceased to believe have only fake emotions to offer,” writes Scruton. “But the faking is pleasant. It feels good to pretend, and when we all join in, it is almost as though we were not pretending at all.”

We find a kind of satisfaction, even in fake emotions. Objectively, this is exactly what is happening when we cease to look beyond fake beauty.

Kitsch is a plague, because it does not take people outside themselves. An encounter with real beauty does. However, kitsch “does not invite you to feel moved by the doll you are dressing so tenderly, but by yourself dressing the doll,” says Sir Roger.

“All sentimentality is like this,” he writes. Encouraged by fake beauty, sentimentality “redirects emotion from the object to the subject, so as to create a fantasy of emotion without the real cost of feeling it.”

Scruton thus exposes fake art: “The kitsch object encourages you to think, ‘Look at me feeling this — how nice I am and how lovable.’”

Making real art is hard work. So is any effort to clear aside the clutter of kitsch, to make room for real beauty in our lives. Thankfully, we don’t have to make the effort all alone, since groups like the Catholic Art Guild exist to accompany us on the journey.

Plato's Euthyphro reflects dilemma about rights

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

A serious philosophical case can be made for the metaphysical reality of rights, writes C.S. Morrissey.

A serious philosophical case can be made for the metaphysical reality of rights, writes C.S. Morrissey.

There is no escape from philosophy. Public debate about euthanasia, abortion, or any controversial issue, will always force us back to the notion of moral rights.

Do we have rights because the state grants them? Or does the state recognize certain rights, because those rights already exist naturally, whether the state grants them or not?

In other words, do rights have a concrete origin in written laws, or does written law strive to express something we know at first abstractly, from reflection on nature?

If we think we have rights because the state grants them, the state becomes like the God of voluntarism, who can invent rights whether they make any rational sense or not. But if we already have rights, whether or not the state recognizes them, then why do we need the state’s clumsy laws?

Given this dilemma, the temptation is to do as the philosopher Alasdair Macintyre does. He dismisses the whole notion of rights as fake, as things that do not exist any more than witches and unicorns do. But a serious philosophical case can be made for the metaphysical reality of rights.

Consider the rigorous arguments of David Oderberg in his excellent book, Moral Theory. A moral right is “a moral power of doing or having something,” and this power is a “capacity or potentiality of doing or having something according to law,” which includes the natural law as well as the state’s written laws, says Oderberg.

This moral power is distinct from physical and legal power. But it is obvious, if physical and legal power is set against these philosophically distinct moral powers, we are in trouble. The moral power is a higher power.

The dilemma about rights is thus somewhat like the dilemma about God depicted by Plato in his dialogue, the Euthyphro. Plato dramatizes Socrates presenting a dilemma to Euthyphro: Is something holy because it pleases God? Or does God find pleasure in it because it is holy?

In the first case, there is no restriction on God to prevent him being pleased with the most horrible actions. In the second case, holiness becomes a higher, external standard, over and against which God’s responses are to be measured.

The discussion in Plato’s Euthyphro ends without a resolution of the dilemma. But the later classical philosophical tradition responded with helpful resources.

For example, Thomas Aquinas made a crucial distinction between primary causality (God’s gift of existence to all things) and secondary causality (anything in the universe acting as a lesser spiritual or material power).

God, as good and holy, is the primary cause. He is always already the source of any goodness and holiness there is, in whatever things exist in the order of secondary causality.

So there can never be an external standard of actuality apart from God, against which he could be measured. The order of secondary causality would not even exist in the first place without God gifting its existence.

His activity uniquely supplies a prior and ongoing action of primary causality. But this does not amount to a nullification of the order and intelligibility in the order of secondary causality.

The universe’s own intelligibility cannot be overridden by the irrational whims of God. God would never wish to redefine good as evil, and evil as good, within the world’s order.

God won’t give a stone to someone who needs bread, or a scorpion to someone who needs an egg, or a snake to someone who needs a fish. He could never find perverse pleasure in acting contrary to his own nature.

He can’t do this, because his nature is pure rationality and pure intelligibility. God himself is the source of any actual perfections in the order of secondary causality. So God himself cannot be anything but at least as ordered and intelligible. God is thus, by his nature, incapable of acting contrary to what is good.

A similar solution can be applied to the dilemma about rights. Rights exist because of the action of primary causality.

The right and good built into nature by the action of primary causality is prior to the state. It is even prior to any action of secondary causality.

Hence any so-called “rights” that would actually contradict the prior order and intelligibility of things, as they actually exist, are not real rights and all.

But when there is an apparent conflict between rights, conflict can be resolved, in principle, on the basis of morality. Morality cannot be internally incoherent, which moral rights would be if they only existed as contingent upon the actions of the state.

Benedictine monks preserve study of Thomism

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

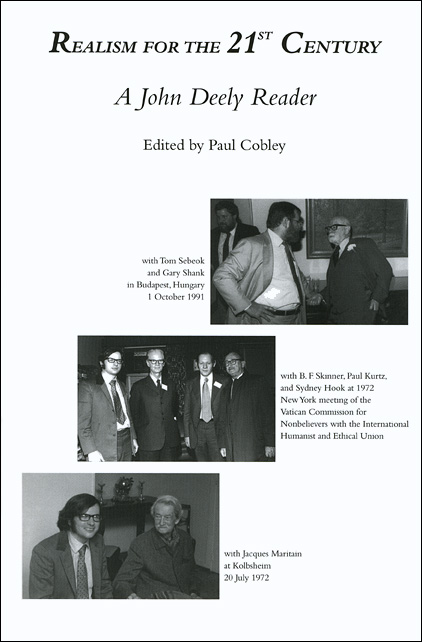

The history behind the John Deely and Jacques Maritain Chair in Philosophy at Saint Vincent College includes a young John Deely (left) meeting with Jacques Maritain in Kolbsheim, France, on July 20, 1972. (Photo courtesy of Brooke Deely)

The history behind the John Deely and Jacques Maritain Chair in Philosophy at Saint Vincent College includes a young John Deely (left) meeting with Jacques Maritain in Kolbsheim, France, on July 20, 1972. (Photo courtesy of Brooke Deely)

Man’s Approach to God was the lecture given by the brilliant Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain in 1951 at Saint Vincent Archabbey. The archabbey, located in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, published Maritain’s three-part lecture in a little book, still in print.

This year the John Deely and Jacques Maritain Chair in Philosophy has been established at Saint Vincent College to serve the archabbey and the hundreds of monks studying there. This new academic post functions to commemorate the life and work of Maritain, but also that of the philosopher John Deely (1942–2017), who passed away this January, and for whom Maritain’s work was so important.

The great Benedictine monk Father Boniface Wimmer (1809–1887) arrived from Rotterdam to New York in 1846. Bishop Michael O’Connor, the first bishop of Pittsburgh, soon extended a fateful invitation to Father Wimmer.

About forty miles east of Pittsburgh, Father Wimmer was able to establish a college and monastery at Saint Vincent parish. The site became the first Benedictine foundation in North America.

Father Wimmer was the first Abbot of the community in 1855 after Pope Pius IX made it an abbey. It was growing rapidly and soon to be the font of many other parishes and abbeys. In 1883, Pope Leo XIII made Father Wimmer into archabbot of the archabbey.

Jacques Maritain delivered his three-part lecture on Man’s Approach to God as the fifth lecture in the Wimmer Memorial Lecture Series at Saint Vincent. The Wimmer Lecture by Maritain is even more economical than the presentation found in his little book Approaches to God, with which it should not be confused.

His lecture’s compact presentation distills key insights from his own magnum opus of philosophy, The Degrees of Knowledge. Maritain speaks in an illuminating fashion about the famous Five Ways of Saint Thomas Aquinas, by which we can come to know God. But he also discusses all the other possible ways human beings can encounter God, through faith and love especially.

With the John Deely and Jacques Maritain Chair in Philosophy, Saint Vincent College is remembering a connection that began back when John Deely was a student working on his doctoral dissertation, reading Maritain’s The Degrees of Knowledge.

Deely found his study of Maritain provided him with what he most needed in his research. Thanks to Maritain, he was able to figure out how to relate the Thomistic account of esse intentionale (“intentional being”) to the discussion of Sein (“Being”) in the philosophy of Martin Heidegger.

This doctoral study eventually became Deely’s first book, The Tradition via Heidegger. Right from the beginning, we see Deely’s fundamental approach to contemporary philosophy’s most interesting problems. That is, we see Deely bringing forth neglected resources from the Thomistic philosophical tradition, to shed light and craft solutions.

Deely dedicated his first book to Maritain. Soon he had the chance to meet his great intellectual mentor on July 20, 1972. The photograph from this visit became a cherished personal possession.

A youthful John Deely with long hair and sideburns smiles looking at the camera, while a beatific Maritain looks at John in a most wonderful way. The picture is printed on the cover of Realism for the 21st Century: A John Deely Reader, edited by Paul Cobley.

Maritain and Deely were both greatly influenced by the masterful commentaries on Aquinas written by the seventeenth century Dominican, John Poinsot. Poinsot is also known as “John of St. Thomas” because of his unparalleled comprehension of Aquinas and his exemplary scholastic treatment of Aquinas’ philosophy and theology.

Besides Maritain, it is hard to think of a greater promoter of the work of Poinsot in the twentieth century other than Deely himself. Thanks to Deely, Poinsot’s own originality can now be appreciated, alongside his fidelity to Aquinas.

Poinsot made original contributions to semiotics, an interdisciplinary field of incalculable importance, which studies the action of signs. For Poinsot, the preeminent examples of sign action would be explored in biblical and sacramental theology.

But Deely learned from his close reading of Maritain how Poinsot’s insights could be extended to all the arts and sciences. The result is nothing less than a revolution in distinguishing and unifying all “the degrees of knowledge,” to use Maritain’s famous phrase.

Saint Vincent College is now home to the over 12,000 volumes from John Deely’s personal library. Visitors to the library can consult a complete set of Maritain’s works, in French and in English, as well as many rare and important books on Maritain and Thomism.

A memorial Mass for Deely on May 8 in Saint Vincent Archabbey Basilica will allow many to give thanks for one of John’s dreams come true: The John Deely and Jacques Maritain Chair in Philosophy at Saint Vincent College.

Spoken poetry offers antidote to digital distraction

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

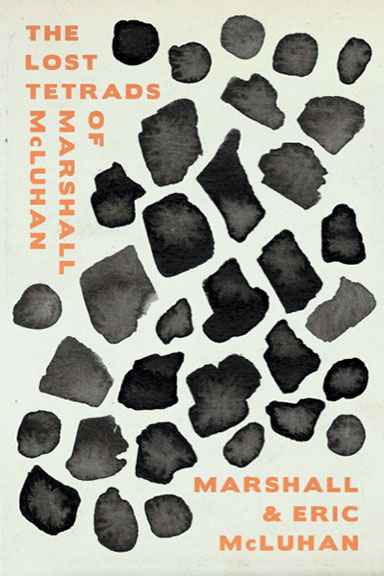

What effect does the new digital technology have on our brains? Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan said it has a hot or cool effect, depending on the hemisphere of the brain to which it appeals, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Image credit: O/R Books)

What effect does the new digital technology have on our brains? Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan said it has a hot or cool effect, depending on the hemisphere of the brain to which it appeals, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Image credit: O/R Books)

Late in life, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan had to undergo brain surgery. It led to him theorizing about the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

Some media experiences are “hot” because they appeal to the left side of the brain. Other media experiences are best characterized as “cool” due to their activation of the right side.

What effect does the new digital technology have on our brains? Social media tosses the human mind into a state of perpetual distraction. It is a shallow experience of the “cool.”

Perhaps the best antidote to such digital distraction is the sacred space of prayerful attention. Extended meditation on the written word can refocus the soul. Think of it as a necessary “hot” experience, much like seeking warmth by a fire.

But as preparation for the prayerful contemplation of scripture, we can also train ourselves to attend to poetry in a “cool” way.

In the digital age, humans are giving themselves over to impulsive reactions to things. But making instant judgments, by “liking” things we think we immediately comprehend, is a very shallow emotional experience.

Deeper access to emotional fulfillment may be found by listening to poetry being recited aloud. Last month I was fortunate to hear theatre and television actor Richard Austin recite from memory the poetry of Father Gerard Manley Hopkins, SJ, in a public performance at Trinity Western University.

Although I had seen and heard Austin do a recitation of Hopkins years ago, I was unprepared for how moved I was this time. Perhaps it is because Austin’s performances of Hopkins have never been better, given that he has slowly and carefully refined them over decades.

Yet in addition to the unsurpassed artistic craft of the performer, I also think it was the unusual experience of hearing poetry aloud that touched my soul. McLuhan would characterize it as a paradigmatically “acoustic” mode of experience.

This appeal to the “ear” is analogous to the simultaneous comprehension of an acoustic space, in which sound is all around us simultaneously. Its primary effect is emotional.

As with the acoustic space created during live music, poetic space is best characterized as holistic. We have to engage in the perception of abstract patterns and to embrace their symbolic dimension.

This requires a willingness to be receptive to the experience, to everything that surrounds us as we undergo it. It is an emotional and creative activity, in which we access our spiritual capacities.

Austin began his performance by reciting Hopkins’ poem Rosa Mystica, about the Virgin Mary, and it was one of four times that evening in which I experienced an intense, involuntary emotional rapture. People refer to this embodied aesthetic reaction in many ways (for example, as getting “goosebumps”), but it is very difficult to describe adequately.

Rosa Mystica has a refrain that repeats, but with variations. For me, it was a sublime, gently electric charge to hear words like this from Hopkins: “In the gardens of God, in the daylight divine / Make me a leaf in thee, mother of mine.”

McLuhan is right, I think, to contrast this “cool” type of “acoustic” experience with the “visual” experience of an “eye” that silently reads words on a page in a linear and sequential order, which appeals to the left side of the brain.

Silent reading is a more analytical experience of human speech, in which verbal access is analogous to mathematical thinking. On the page, in print, we subjugate words in a detailed and controlled way. But this intellectual control, with its mode of domination over the word, is wholly unlike the involuntary emotional reaction we are capable of accessing by hearing live poetry.

Along with As Kingfishers Catch Fire and The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo, I also experienced emotional bliss when I heard the words of Hopkins’ The Windhover.

McLuhan considered Hopkins’ greatest poem to be The Windhover. “There is no other poem of comparable length in English, or perhaps in any language, which surpasses its richness and intensity or realized artistic organization,” argued McLuhan.

“There are two or three sonnets of Shakespeare,” and one by Donne, that may rival it, wrote McLuhan, but yet “they are not comparable with the range of the experience and multiplicity of integrated perception” of The Windhover.

To hear The Windhover live is unforgettable. The “hot” experience of reading it silently cannot compare with the “cool” sensation of hearing it performed.

As McLuhan recognized, the “acoustic” experience of “the delicate interaction, at each moment of the poem, of all its cumulative vitality of logic, fancy, musical gesture” is nothing less than astonishing.

Catholic poet conveys sacramental view of world

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

It is spellbinding when theatre and television actor Richard Austin performs live, from memory, the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, writes C.S. Morrissey.

It is spellbinding when theatre and television actor Richard Austin performs live, from memory, the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, writes C.S. Morrissey.

“Nothing is so beautiful as Spring,” exclaims 19th-century poet Father Gerard Manley Hopkins, SJ, at the beginning of his gorgeous and astonishing poem Spring.

Theatre and television actor Richard Austin has dedicated great efforts to reciting the poetry of Hopkins in public performance.

Although he has made an excellent recording (“Back to Beauty’s Giver”) of his readings of a number of Hopkins’ verses, Austin also keeps alive the pre-modern experience of memorizing vast amounts of Hopkins’ poetry for public recitation.

A few years ago, I experienced one of Austin’s performances. The effect is spellbinding. When Hopkins’ poetry comes to life, the thrill in the room is palpable.

In our digital age of Internet distraction, not many people memorize great poetry anymore. But there is an unmistakable difference between watching a YouTube video, and being in the same room with a human being whose voice and body incarnates poetic magic.

Just as Hopkins had converted to Catholicism, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan also converted to Catholicism as a young man. Both men were in their twenties when they did so.

Before he became famous in the 1960s and 1970s for his analysis of how media and advertising are turning our planet into a “global theatre,” McLuhan was an English professor who wrote about topics like the magnificent poetry of Hopkins.

In an essay called The Analogical Mirrors, published in The Kenyon Review in 1944, McLuhan observes, “The Catholic reader has the advantage only in that he is disposed to give Hopkins a chance.” Otherwise, because of his use of analogy, Hopkins can make accessible, to a reader of any background, “a sacramental view of the world.”

By this McLuhan means “what of God is there” in Hopkins’ poetry is something that Hopkins “does not perceive nor experience but takes on faith.” In other words, Hopkins is not the sort of poet who is “a nature mystic at all, nor a religious mystic” reporting back to the reader a secret experience.

Instead, McLuhan argues, Hopkins is “an analogist.” That is, he simply uses language and analogies in order to convey the sacramental mode of vision by which faith looks at the world. It is “by intensity and precision of perception” and “by analogical analysis and meditation” that Hopkins “achieves all his effects,” writes McLuhan.

“It may sound at first strange to hear that Hopkins is not a mystic but an analogist,” he concedes. Yet Hopkins “does not lay claim to a perception of natural facts hidden from ordinary men,” as a nature mystic would. This accessible stance toward nature “is evident in every line of description he ever wrote,” contends McLuhan.

Moreover, the religious experience of Hopkins, conveyed by his poetry, is not the inaccessible experience of a religious mystic. “Nowhere in his work does he draw on an experience which is beyond the range of any thoughtful and sensitive Catholic who meditates on his Faith,” observes McLuhan.

Thus, anyone who hears the poetry of Hopkins does not need a hidden mystical experience, natural or religious, in order to relate to it. Instead, Hopkins’ innovative wordplay simply “records a vigorous sensuous life in the order of nature,” says McLuhan, which we are all capable of experiencing, for example in the experience of springtime.

Hopkins’ poetry “deals sensitively with the commonplaces of Catholic dogma,” but it is a mistake to call such poetry “mystical,” argues McLuhan. For any believer, who sees with the eyes of faith, a sacramental vision of the world is readily accessible.

With his vision, Hopkins possesses an incredible intensity of perception. Yet McLuhan remarks how Hopkins uses “a relatively small number of themes and images” to exhibit “an infinitely varied orchestration” of them.

A public performance of Hopkins’ poetry is thus never disjointed. Instead, it uniquely conveys the holistic experience of a sacramental vision. “Familiarity with Hopkins soon reveals that each of his poems includes all the rest, such is the close-knit character of his sensibility,” writes McLuhan.

To write about a Hopkins poem involves “an inevitable dispersal of attention,” says McLuhan. “But then only an oral reading with all the freedom and flexibility of spoken discussion can really point to the delicate interaction, at each moment of the poem, of all its cumulative vitality of logic, fancy, musical gesture.”

Scientist and theologian discuss human origins

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

According to Father Joseph Fitzmyer, Adam in Genesis is a symbolic figure denoting humanity, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Photo: Brazos Press)

According to Father Joseph Fitzmyer, Adam in Genesis is a symbolic figure denoting humanity, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Photo: Brazos Press)

A new book is exploring human origins and “the historical Adam.”

Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture After Genetic Science (Brazos Press, 2017), by biologist Dennis Venema and theologian Scot McKnight, explores the recent scientific discovery that “we descend from a population of about 10,000 individuals rather than a pair.”

The book wisely avoids trying to solve every theological problem raised by the discoveries of population genetics. Instead it focuses on establishing (in the first four chapters by Venema) what we now know about the history of human beings and (in the last four chapters by McKnight) our theological options for understanding Adam.

Venema, the scientist, draws upon his professional expertise in genetics as well as his life experience, in which he learned how to reconcile evolution with his Christian faith. He explains the truth about evolution as a scientific theory and, in an engaging style, teaches the reader about genomes by drawing helpful analogies with books and languages.

Part of Venema’s life story includes his coming to see how the “intelligent design” critique of evolution, to which he was drawn at first, cannot be reconciled with the data. This fascinating part of his presentation will no doubt prove helpful to others struggling to reconcile the Bible with modern science. Venema has a patient and charitable way of calmly dealing with the truths we are able to know from biology.

Like Venema, the theologian McKnight also refrains from undue speculation, offering instead a basis for theological inquiry going forward. In his chapters, he helpfully presents four principles for reading the Bible in light of what we now know from the Human Genome Project, and proposes twelve clear theses about how to properly understand the Adam and Eve of Genesis in their context.

In addition, to further guard against theological misunderstandings of the Genesis text, McKnight also provides a highly informative overview of the variety of Adams and Eves in the Jewish world. This eye-opening chapter includes discussions of Adam in seven different texts and writers: the Wisdom of Sirach, the Wisdom of Solomon, Philo of Alexandria, the book of Jubilees, Flavius Josephus, 4 Ezra, and 2 Baruch.

Concluding the book with the Apostle Paul’s treatment of Adam in the book of Romans, McKnight presents his own theological conclusions about “the historical Adam.” To his credit, McKnight draws upon the work of the great Catholic biblical scholar Father Joseph Fitzmyer, SJ, who died recently in December 2016.

McKnight approvingly quotes Fitzmyer, who notes: “Paul treats Adam as a historical human being, humanity’s first parent, and contrasts him with the historical Jesus Christ. But in Genesis itself Adam is a symbolic figure, denoting humanity.” In other words, “Paul has historicized the symbolic Adam of Genesis.”

The theological point here seems to be that historicizing something does not make it historical. For example, the writers of Star Trek can make Kirk, Spock, and McCoy time-travel to a real historical time and place. But just because they can historicize the characters does not mean that those literary figures are historical people.

Although Paul was clearly historicizing Adam when he compared him to Christ, Fitzmyer writes: “Paul, however, knew nothing about the Adam of history. What he knows about Adam, he has derived from Genesis and the Jewish tradition that developed from Genesis. ‘Adam’ for Paul is Adam in the Book of Genesis; he is a literary individual, like Hamlet, but not symbolic, like Everyman. Adam is for Paul what Jonah was for the evangelist Matthew (12:40) and Melchizedek for the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews (7:3). All three have been used as foils for Christ. But they are literary figures who have or have not been historicized, as the case may be.”

Although he follows Fitzmyer on this, McKnight’s own Protestant convictions apparently lead him to reject any reading of Romans 5:12 (“sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned”) that would interpret it as supporting the theological idea of “original sin.”

McKnight writes, “The early church father Jerome, ever fiddling with the text and not so good in Greek, translated ‘because [eph’ ho] all sinned’ as ‘in whom [in quo] all sinned,’ then Augustine made nothing less than an extensive case for the theory of original sin and original guilt, and we’ve been stuck with both of them and that theory ever since.” But McKnight thinks, “Humans somehow inherit something from Adam, but they die not because of that inheritance but because they sin.”

Yet this seems to be a hasty oversimplification. McKnight’s denigration of Jerome is bizarre, since Jerome’s Latin translation is literally accurate. Moreover, the Latin in quo need not mean “in whom,” but could also be construed, just like the Greek eph’ ho, to mean “on the basis of which” (as Theodor Zahn has argued, which is also my preferred translation of the Greek). Finally, McKnight’s dismissal of Fitzmyer’s own maverick translation of the phrase (Fitzmyer renders eph’ ho as “with the result that”) is likewise too hasty.

However, the great merit of this book is still evident. It highlights many of the most important aspects of the scientific and theological discussion about Adam. Although its theological treatment seems tailored to a Protestant audience, Catholics can still learn much from it, especially its brilliant discussion of genetic science.

Dr. C.S. Morrissey cultivates classical tradition by teaching the Greek and Latin classics. Learn more about the classics at moreC.com.

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

Jesus teaches nonviolence as an active way to resist and overcome oppression and violence, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Picture credit: Norton Simon Art Foundation, Christ Crowned with Thorns by Matthias Stom)

Jesus teaches nonviolence as an active way to resist and overcome oppression and violence, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Picture credit: Norton Simon Art Foundation, Christ Crowned with Thorns by Matthias Stom)

One of the most eye-opening books you can read is Jesus Christ, Peacemaker: A New Theology of Peace, by Terrence J. Rynne, a peace studies professor at Marquette University.

Rynne describes how “love your enemies” is central to the teaching of Jesus. It is not meant to be a vaguely pious sentiment, a utopian thought rarely implemented by realists. Jesus actually trained his disciples to understand and live the way of peace as a revolutionary daily practice.

Jesus does not endorse “pacifism” as a kind of passivity that simply lets evil happen without response. Instead, Jesus’ approach is better termed “peacemaking,” which means a wholehearted activity. The word “peacebuilding” also nicely highlights the diligence and intelligence his approach requires.

Jesus teaches nonviolent resistance as the active way to overcome violence. Rynne rightly sees that the Greek verb antistenai means “violent resistance” in the following passage from the Sermon on the Mount:

“You have heard it said, an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, but I say to you, do not violently resist [antistenai] one who does evil to you. If anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the left; if someone goes to court to take your coat, give him your cloak as well; and if anyone presses you into service for a mile, go a second mile.” (Matt. 5:39-41)

Jesus is giving concrete advice for creative nonviolent resistance in each of these three situations. Rynne explains how, in the first situation, being struck on the “right cheek” indicates the attacker is using the back of his or her right hand to inflict the blow. Jesus’ original hearers would have understood this reference to a culturally specific way of delivering a humiliating insult.

Notice how Jesus advises the person who was struck. He does not say one should submit with resignation to a backhanded slap. One should not accept the gesture, because it attempts to express who is dominant and in charge as the “superior,” and who is submissive and in the position of an “inferior” expected to take the abuse.

Instead, Jesus counsels nonviolent resistance. He advises the person who was slapped to stand up for themselves. By offering the other cheek, they would be saying they are equal in humanity with the other person: they do not accept the submissive role that the violent bully wants them to accept.

Most importantly, Jesus is advising them not to respond in kind with reciprocal violence. By boldly presenting one’s left cheek to the backhanded slapper’s right hand, one is daring the attacker to attack them again, but as a social equal: with a direct punch to the face, rather than letting them deliver a backhanded slap to a social inferior, whom they expected to accept their bullying.

It’s an unexpected gesture meant to shock the attacker with its boldness. Rather than responding with an escalation of violence, it’s a creative expression of nonviolence. It demonstrates how good is more courageous than evil. And it tries to “win over” evil with the greater spiritual strength that nonviolence displays: I am willing to risk additional pain, a fist to my face, to reach you with a message about our common humanity. You cannot intimidate me. Your insults are futile gestures. But I demonstrate my own dignity, by not striking you back.

Jesus’ other two examples similarly turn the tables on violence and oppression. Jesus considers someone so poor, they have nothing they can be sued for except the coat on their back: he advises them to demonstrate the absurdity of such merciless persecution by stripping naked and offering their undergarments too. Hilariously effective!

A Roman soldier had the right to make someone in the country they were occupying carry their pack. But the soldier’s centurion would place a limit of one mile on such enforced service, in order to limit the resentments of the subjugated population in the occupied territory.

Thus, Jesus’ advice hilariously subverts the unjust situation, since the soldier might get in trouble with his centurion if someone were to go a second mile. Or, the act of nonviolent resistance could simply win over the soldier with its good-natured, humorous appeal to their common humanity: I do not treat you as you treat me, with oppression; instead, I have some fun with you, and humanly connect with you.

Loving your enemy means so much more than than you originally thought. Let Jesus Christ, the Peacemaker, show you the way to be fully human.

Dr. C.S. Morrissey cultivates classical tradition by teaching the Greek and Latin classics. Learn more about the classics at moreC.com.

Legal philosophy must use right reason to defend rights of innocent

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

There are such things as inalienable rights, and the legal profession should be passionately devoted to defending them, writes C.S. Morrissey.

There are such things as inalienable rights, and the legal profession should be passionately devoted to defending them, writes C.S. Morrissey.

A new television program celebrates a doctor who is secretly killing people. Her devotion to euthanasia is not shown to be something horrific. Instead, to elicit our sympathies, she is portrayed as an overworked single mother.

It is dismaying to see such propaganda. By submitting themselves to such blatant emotional manipulation, viewers will come away with no good reasons not to be in favor of euthanasia.

“The law is reason free from passion,” wrote Aristotle in his Politics. As if in disagreement, the movie Legally Blonde celebrated the story of a woman who used her passion to become a better lawyer.

But now we have a doctor who is passionate about euthanasia. To make her the hero of a television program, and to depict her sympathetically, is a deeply sinister cultural development.

Aristotle would have no quarrel with lawyers who, in order to do good things, tap into the power of the emotional side of human nature. After all, in his famous ethical treatise, the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argued we cannot be truly moral unless our desires harmonize with right reason.

Yet euthanasia is supported by a philosophy that is deeply irrational. We need to harness the power of right desire, but this means our desires must be in accordance with right.

Doctors who, in order to do bad things, tap into the power of emotion, are morally bad. In order to oppose them, we need lawyers who, like Elle Woods in Legally Blonde, are passionate defenders of laws that are in accordance with right reason.

To oppose euthanasia, they will need to have the best philosophical resources. A solid legal philosophy will recognize that the right to life is inalienable.

In his brilliant book, Moral Theory: A Non-Consequentialist Approach, the philosopher David Oderberg supplies solid arguments on behalf of traditional moral philosophy.

Oderberg subjects to rational scrutiny the grave moral evil of those who, with deliberate intent, would take away innocent human life. This eminently reasonable book concludes with a stirring defense of the doctrine of the sanctity of life.

In a companion volume, Applied Ethics: A Non-Consequentialist Approach, Oderberg applies this traditional moral philosophy, recognizing that the purpose of justice is always and everywhere to defend the rights of the innocent.

Concerning euthanasia, he writes it would be “a mistake to claim that we are at the edge of a slippery slope to mass murder.” What he means is our situation is even more disturbing: “We are on that slope,” he writes. Moreover, because we can make people live longer and then harvest their organs, “we have technology and expertise far in advance of anything available to the Nazis.”

Since they never learn a fully rational medical ethics, doctors are now “becoming servants of the state hired to maximize utility,” rather than defenders of the lives of the innocent.

What is most disconcerting about this development is the fact that, as Oderberg writes, “the state and the judicial system, which give implicit and progressively explicit support to euthanasia, have far greater powers, both to persuade and to execute policy, than those possessed by the Nazi state.”

Oderberg quotes Dr. Leo Alexander, a psychiatrist who was consulted by the U.S. Secretary of War at the Nuremberg trials for war crimes. In 1949, Dr. Alexander observed about the Nazi crimes that it “became evident to all who investigated them that that they had started from small beginnings.”

“The beginnings at first were merely a subtle shift in emphasis in the basic attitude of the physicians,” said Dr. Alexander. “It started with the acceptance of the attitude, basic in the euthanasia movement, that there is such a thing as life not worthy to be lived.”

Again today we are being subjected to blatant propaganda about some lives not being worth living. “This attitude in its early stages concerned itself merely with the severely handicapped and chronically sick. Gradually the sphere of those to be included in this category was enlarged to encompass the socially unproductive, the ideologically unwanted, the racially unwanted and finally all non-Germans.”

Dr. Alexander warned, “it is important to realise that the infinitely small wedged-in lever from which this entire trend of mind received its impetus was the attitude toward the non-rehabilitable sick.”

As Oderberg demonstrates in his books, while this attitude has considerable emotional appeal, it is deeply irrational. There are such things as inalienable rights, and the legal profession should be passionately devoted to defending them.

Now more than ever, the right to life needs philosophically informed defenders.

Dr. C.S. Morrissey cultivates classical tradition by teaching the Greek and Latin classics. Learn more about the classics at moreC.com.

JOHN DEELY (1942-2017): Philosopher gained insights from medieval thinking

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

John Deely, who passed away Jan. 7, demonstrated how we need to recover key insights from medieval philosophy in order to cure the ills of modern thought, writes C.S. Morrissey.

John Deely, who passed away Jan. 7, demonstrated how we need to recover key insights from medieval philosophy in order to cure the ills of modern thought, writes C.S. Morrissey.

Four Ages of Understanding, by the intrepid Catholic philosopher John Deely, recovers the history of philosophy in an astonishing way. It demonstrates how we need to recover key insights from medieval philosophy, in order to cure the ills of modern thought.

Even though our friend John passed away on Jan. 7, it is one of many truly great books that will live on.

John was born in Chicago on April 26, 1942. He studied at the Pontifical Faculty of Philosophy of the Aquinas Institute of Theology in River Forest, Illinois. The amazing Dominicans there, like Benedict Ashley, OP, were among the teachers who formed him for a lifetime. He received his PhD in 1967.

He soon moved on from various academic posts to his first major career accomplishment: to work closely with the renowned philosopher Mortimer Adler, at the Institute for Philosophical Research, from 1969 to 1974.

A fruitful philosophical disagreement between Deely and Adler resulted in John going his own way. He needed to continue unhampered his investigations into the history of semiotics in the Middle Ages: i.e., how philosophy and theology tried to explain the functioning of biblical and sacramental “signs.”

“I am indebted to him and regret that unresolved differences of opinion between us about certain aspects of a theory that we otherwise share prevent him from associating his name with mine in the authorship of this book,” wrote Adler in the preface to Some Questions about Language: A Theory of Human Discourse and Its Objects (1976), which they had originally begun writing together.

Adler was a noted advocate of the “Great Books” and “Great Ideas” approach to education. But John continued his intense and innovative work on the problem of “signs” in philosophy as he went on from Adler’s Institute to work as full Professor at Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa (1976–1999).

In 1999, John switched his institutional home base to the Center for Thomistic Studies, at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas. At that time, our Archbishop Miller was there, serving as the university’s president. At the center, Deely held the Rudman Chair of Graduate Philosophy from 2007 to 2015.

From 2015 to the time of his death, John was Philosopher in Residence at St. Vincent Archabbey College and Seminary in Latrobe, Pa. An unexpected battle with cancer cut short his plans to revamp their philosophy department.

John was an original thinker who made great contributions, writing more than 30 important books and more than 200 specialized academic articles. He was able to innovate because he had acquired a solid grounding within the Catholic intellectual tradition.

The great French Catholic Thomist Jacques Maritain was an influence on both his professional and personal life. At a meeting of the American Maritain Association, he met his wife Brooke Williams Deely. Many know her as the scholar behind the book Pope John Paul II Speaks on Women (2014), but back in 1986 she worked with John on Frontiers in Semiotics.

Professor Michael Torre of the University of San Francisco, a past president of the American Maritain Association, recalls that “John and Brooke remained loyal to the American Maritain Association,” as John was “a founding member and perhaps even the chief architect of its first Constitution.”

“He attended its meetings for some 40 years. He was deeply admired by many of its members: not merely for his mental acuity and creativity, but also for his deep thoughtfulness and intellectual humility,” remembers Torre.

“He managed to be nova et vetera in the very best sense of that phrase. Beyond his virtues, he simply will be missed by many as their good friend, one who it ever was a joy to be with. His strong presence, his wit, and his laughter will be sorely missed at the gatherings of those colleagues who were devoted, as he faithfully was, to Jacques Maritain.”

John’s most important philosophical contributions included his promotion of the works of John Poinsot who, as one of the very greatest commentators on St. Thomas Aquinas, is also known as John of St. Thomas.

The community of Benedictine monks at the Abbey of Solesmes is the publisher of the critical edition of Poinsot’s writings. Jacques Maritain was a Benedictine Oblate for whom Poinsot was the most beloved Thomistic guide.

Deely meticulously prepared a bilingual edition of John Poinsot’s Tractatus de Signis (“Treatise on Signs”), which upon publication received the featured book review in The New York Times (Easter, 1986). To keep this important work in print, St. Augustine’s Press recently printed a second edition.

John Hittinger, current holder of the Rudman Chair at the Center for Thomistic Studies, notes John’s work will live on: “John Deely crafted a fresh approach to the thought of Thomas Aquinas through a development of the notion of sign and he developed an authentic ‘post modern’ philosophy surmounting the empiricist/rationalist and realist/idealist dichotomies of the modern age.”

“Deepening the semiotic work of Jean Poinsot and Charles S. Peirce,” explains Hittinger, “Deely showed philosophers a way forward beyond the interminable debates about subjectivity and objectivity, nature and culture, inner and outer dimensions. His legacy will continue to enrich Thomistic philosophy and to prove beneficial across many traditions, cultures and historical perspectives.”

Epic trilogy reveals the history of 'gender ideology'

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

In the grand finale to her epic scholarly trilogy, Sister Prudence Allen contrasts the Catholic idea of gender reality (integral gender complementarity) with the various versions of the gender unity or gender polarity theories, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Photo credit: Eerdmans)

In the grand finale to her epic scholarly trilogy, Sister Prudence Allen contrasts the Catholic idea of gender reality (integral gender complementarity) with the various versions of the gender unity or gender polarity theories, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Photo credit: Eerdmans)

In Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, we learn the hidden history behind the story of the first Star Wars trilogy. The Rebel Alliance acquires the plans to the Death Star, thanks to the heroic mission of Jyn Erso (Felicity Jones).

Thanks to Sister Prudence Allen, RSM, we also learn this year about the hidden history behind what she calls “gender ideology.” The final volume of her scholarly trilogy The Concept of Woman has just been published, Volume III: The Search for Communion of Persons, 1500-2015.

Pope Francis has also been using the term “gender ideology,” which Sister Allen uses in her writings to refer to “a deconstructionist approach to the human person as a loose collection of qualities, attributes, or parts.” This approach is driven by “a revisionary metaphysics” that does not make an accurate description of what Sister Allen calls “gender reality.”

The complexity of the question, which involves all of today’s most heated debates about man and woman, is reflected in the lengthy academic treatment of The Concept of Woman’s three volumes. Sister Allen’s work patiently describes the philosophical history in the West of the concept of woman in relation to man.

Because she has carefully explored thousands of years of history, her work has taken over three decades to research and publish. Eden Press published the first volume in Canada in 1985. Since 1997, it has been published by Eerdmans, which keeps it available through print on demand.

Volume I, The Aristotelian Revolution, 750 B.C. - A.D. 1250, studies “the paradoxical influence of Aristotle on the question of woman,” because of that Greek philosopher’s complex influence on philosophical discussions about the notion of “sexual complementarity.”

Whatever Aristotle’s own views may have been, his writings had the historical effect of lending support to the “sex polarity” concept of woman, in which woman is viewed as inferior to man. Woman comes to be thought of as the polar opposite of man, who is taken to be superior.

In contrast with Aristotle’s influence, the other main historical concept of woman can be traced back to Plato, whose writings were taken to justify a “unisex” concept of woman. According to the “unisex” theory, man and woman are equal because they are not significantly different, and there is only a spectrum of difference along one essential gender type of being “human.”

Sister Allen considers both approaches to be distorted, since they can easily be used to justify gender ideologies that do not correspond to the reality of woman and man. She describes the reality as “integral gender complementarity,” by which man and woman are complementary to one another, but “complementary as wholes.”

Published in 2002, Volume II, The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250-1500, traces the complex ideas of “gender complementarity” in the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, contrasting them with the many variations on the “unisex” and “sex polarity” ideas. This volume was so large, it was split into two books (Volume II, Part 1 and Volume II, Part 2), although it has also been published together as one gigantic volume over 1,100 pages long.

This reminds me of St. Thomas Aquinas’ epic trilogy, the Summa Theologiae, which also has a second part split into two parts: the Prima Secundae Partis (I-II: “the first part of the second part”) and the Secunda Secundae Partis (II-II: “the second part of the second part”).

Many fans of the original Star Wars trilogy consider the second part, The Empire Strikes Back, to be the best part of the trilogy. Although it is too early to tell, because it has just been published, readers may end up liking the third part of The Concept of Woman the best.

In Volume III, Sister Allen goes into greater detail about the historical development of the Catholic idea of “gender reality” (namely, “integral gender complementarity”), which she contrasts with the various versions of the “gender unity” or “gender polarity” theories.

Pope Francis appointed Sister Allen as one of five women on the International Theological Commission, which advises him on difficult theological matters. Although she is not a theologian, her expertise in the philosophical history of the concept of woman makes her an excellent member of the team.

Readers intimidated by the size of her magnum opus, The Concept of Woman, can choose instead to read the slim volume to which she contributed along with Pope Francis, Not Just Good, but Beautiful, which opposes any “gender ideology” that would resemble the Death Star in its capacity to harm the innocent.

Dr. C.S. Morrissey cultivates classical tradition by teaching the Greek and Latin classics. Learn more about the classics at moreC.com.

Austrian priest makes powerful case for pacifism

BY C.S. MORRISSEY

You Shall Not Kill is an inspiring book by the Austrian priest and university professor Johannes Ude (1874-1965) explaining the rationale for nonviolence, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Photo credit: Wipf and Stock)

You Shall Not Kill is an inspiring book by the Austrian priest and university professor Johannes Ude (1874-1965) explaining the rationale for nonviolence, writes C.S. Morrissey. (Photo credit: Wipf and Stock)

Between 1941 and 1944, under constant threat of death from Hitler’s dictatorship, Austrian priest and university professor Johannes Ude clandestinely penned You Shall Not Kill.

When Ude was charged with treason and imprisoned by the Nazis for a second time, from August 1944 to April 1945, he almost starved to death. But the approach of Allied troops saved his life.

Before his imprisonment, Ude had entrusted his book to the artist Hanns Kobinger, who kept it from falling into the hands of the Gestapo. The book makes a powerful and persuasive argument that followers of Jesus Christ should imitate their Lord by living a life of total nonviolence.

Cascade Books, an imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers, has just published You Shall Not Kill in an excellent English translation by Ingrid M. Leder. Included is Kobinger’s original foreword to the book. But now there is also a foreword, written especially for the English edition, by the prolific Catholic historian Ulrich L. Lehner.

As the author of books like The Catholic Enlightenment: The Forgotten History of a Global Movement (Oxford University Press, 2016), Lehner is somewhat of a specialist in histories of mavericks and visionaries like Ude.

“There was probably not a more educated Catholic theologian in the twentieth century than Ude,” argues Lehner. The claim may seem shocking, but Lehner points out that neither Hans Urs von Balthasar nor Karl Rahner had the five doctorates Ude did.

Ude first earned doctorates in philosophy and theology, then a third in dogmatic theology, a fourth in biology, and a fifth in economics. The astounding range of Ude’s learning is on display in the brilliant argumentation of You Shall Not Kill, which comprehensively reviews both sides of the dispute over nonviolence.

The first 40 pages cover traditional Catholic teaching on the commandment not to kill. Ude shows how, in accordance with reason and natural law, moral philosophy must arrive at the absolute rejection of abortion, suicide, sterilization, and the killing of terminally ill or mentally disabled persons.

Ude also explains the arguments that justify violence when employed under such forms as the death penalty and self-defence, as well as in limited defensive warfare according to the “just war” tradition.

Yet Ude then proceeds, in an extended treatment of over 200 additional pages, to argue against the traditional justifications for the death penalty, self-defence, or military action. He rejects conscription, military service, and any form of warfare whatsoever. He even includes an explanation about why many people committed to nonviolence become vegetarians.

Nominated 12 times for the Nobel Peace Prize, Ude was a significant figure in the international pacifist movement.

Yet many people are still skeptical about what quality of arguments could possibly be given to defend nonviolence. Common sense seems to endorse the notion that sometimes Christians must fight. Yet Ude makes a powerful case that should be read by anyone who dares, in any way, to reject the divine commandment not to kill.

At the very least, one should not reject nonviolence if one does not yet understand its full rationale. Reading You Shall Not Kill is a great way for anyone to learn how the most educated Catholic of the 20th century makes the strongest possible case for peacebuilding.

Anyone who wants to change their life for the better, and to be inspired to make a real difference in the world, will be encouraged by this book.

Nonviolence is also commended in the message of Pope Francis for the 50th World Day of Peace on Jan. 1, 2017: “A Style of Politics for Peace.”

“I ask God to help all of us to cultivate nonviolence in our most personal thoughts and values,” Francis writes. By embracing Jesus’ teaching about nonviolence, says the Pope, we become his true followers.

Francis exhorts us each to personally cultivate “peacebuilding through active nonviolence,” and yet he also encourages a comprehensive cultural shift toward peacebuilding:

“This is also a programme and a challenge for political and religious leaders, the heads of international institutions, and business and media executives: to apply the Beatitudes in the exercise of their respective responsibilities.”

It is the ultimate New Year’s resolution: “In 2017, may we dedicate ourselves prayerfully and actively to banishing violence from our hearts, words and deeds, and to becoming nonviolent people and to building nonviolent communities that care for our common home.”

Nonviolence is not impossible, says the Pope: “Everyone can be an artisan of peace.”

Dr. C.S. Morrissey cultivates classical tradition by teaching the Greek and Latin classics. Learn more at moreC.com.